By Joe Daniel. Defensive Coordinator and Offensive Line Coach,

Prince George High School (VA)

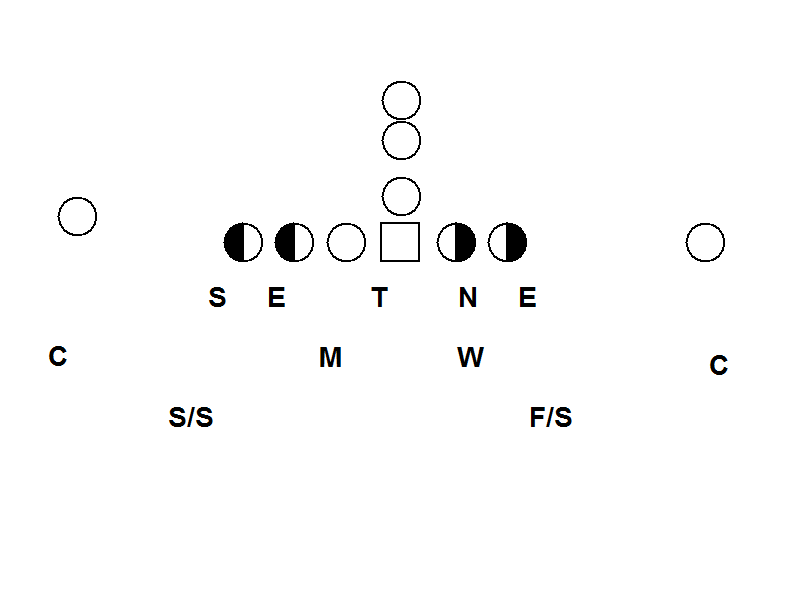

The Miami 4-3 Defense originated in the mid-1980s at the University of Miami. The original concept was designed to stop the Wishbone Option (Diagram1). The design was incredibly flawless. Even with the evolution of offense in the last 30 years, the original linebacker keys still hold true against any offensive set Diagram 1

In the beginning, the 4-3 defense was primarily used with cover 2. The cornerbacks were the force players. We use quarters coverage, and the safeties are the force player on most snaps. Because we are not rolling a safety down, the way that 4-3 defenses using cover 3 would do, we must 2-gap our linebackers.

2-gap linebackers may sound scary and complicated at first. The keys, reads and rules of the 4-3 defense make this process natural, though. The reaction to our primary and secondary keys puts our linebackers in the right place.

Keys for the Mike Linebacker

Our Mike Linebacker is a hard-nosed football player. He is going to be in a collision repeatedly, particularly against two-back football teams. We begin teaching all of our reads against 21 personnel, but little changes when we start seeing more one-back offenses and spread formations.

Against two-back formations, the Mike linebacker will always key the Fullback. We tell him that he is married to the fullback all night long. He is aligned in a weak 10 technique, directly behind the weak-shaded nose. We place him there because he is responsible for the A Gap on the strong side or B Gap on the weak side, depending on the direction of the play.

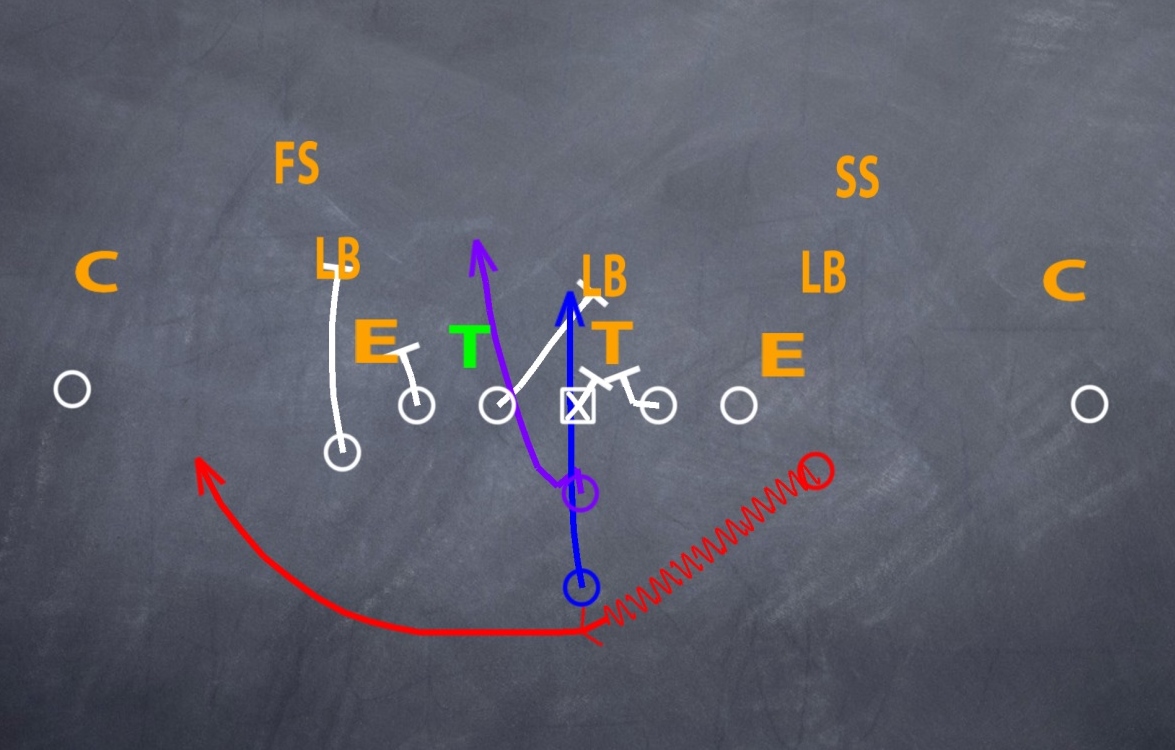

The fullback takes him to his initial two steps. If the fullback shows hard flow strong, the Mike linebacker heads towards the A gap strong (Diagram 2). If the fullback shows hard flow weak, the Mike linebacker steps to the B gap weak (Diagram 3).

On his way, the Mike now picks up the movement of the offensive guard on the side the fullback headed. If he sees the guard pull in the opposite direction, he immediately plants his outside foot and drives back to his gap responsibility on the other side. For example, on a counter play, he might see the fullback step weak to kick out the defensive end. The guard and tackle pull across his face though, telling him to redirect to A gap strong.

Keys for the Outside Linebackers

Our Sam and Will linebackers should be interchangeable players. They will often walk out of the box against spread formations (particularly the Sam), so the outside linebackers should be quicker and more athletic than the Mike linebacker. The Mike takes on the brunt of the punishment, so the outside linebackers will rarely take on lead blocks.

The outside linebackers are keyed on the tailback, or primary ball carrier. They must also be able to pick up guard pulls after their initial backfield read. If the Tailback shows hard flow strong, the Sam linebacker looks to fill the C Gap strong. The Will Linebacker will use a shuffle technique to check for counters and cutbacks. Once the ball declares into the line of scrimmage, the Will linebacker gets into his pursuit angle. He will not cross the center until the ball declares.

When the tailback shows hard flow weak, the Will linebacker uses a spin down technique. Because the Mike linebacker fills the weak B Gap on flow weak, the Will is going to shuffle down behind the defensive end and fit as needed. If he sees daylight inside, in the B gap, he will fit there. If the Mike has successfully clogged the B gap, the Will fits tight to the outside hip of the defensive end.

The Sam Linebacker on hard flow weak plays for the cutback before getting into his pursuit. angle.

Adjusting to Fast Flow

We use hard flow to refer to runs between the tackles. Fast flow tells us that the ball is being taken outside of the tackles. On fast flow, we gap exchange to adjust to the play.

On a fast flow strong, the Sam linebacker attacks to the outside. He fits tight to the hip of the defensive end, who is most likely fighting a reach block. The Mike linebacker takes the run through in C Gap, where the Sam linebacker would normally fit. Because the Will Linebacker has no threat of a cutback, he immediately gets into his pursuit path (Diagram 4)

With fast flow weak, the fits are similar. With no threat of an inside run, the Will linebacker immediately fits to the outside of the defensive end. The Mike linebacker takes his run through in the weak side B Gap. Because there is no threat of a cutback, the Sam linebacker gets into his pursuit angle immediately (Diagram 5).

Remember that the safeties are the contain players in quarters coverage. As long as they can force the play to slow down, the linebackers and defensive ends can run it down. Our Mike linebacker makes a majority of tackles on outside run plays, as long as the safeties do their job.

Split Flow and Dive Flow

Our final two backfield keys are split flow and dive flow. Each presents unique challenges for the defense. The original design of the Miami 4-3 defense adapts to both.

Split flow occurs when the fullback goes one direction, and the tailback heads in the other direction. As we mentioned when talking about the Mike linebacker’s fits, the secondary key is critical in defending split flow. The secondary key for our linebackers is guard pulls (Diagram 6).

We teach our linebackers to read both backfield keys and guard keys. While we do find some linebackers are more comfortable focusing on guard reads (particularly shorter linebackers who have trouble seeing into the backfield), we focus on teaching the backfield as the primary key and the guards as a secondary key. Pulls and high hat reads by the linemen give our players the final clue to the play they are defending.

Any time that a guard crosses the sight line of our linebackers, they plant their foot and redirect in the direction of the pull. We teach this step as a Rock ‘n Roll footwork. They plant hard on the outside foot and roll their weight back to the opposite side of the play.

A significant challenge for our reads is the inside zone play. The fullback often kicks out the defensive end, but there is no puller to pick up. When we play a strong inside zone team, we take time to rep the play and fill up our gaps. If the offensive linemen’s shoulders are staying square against an inside zone team, the Mike fills the strong A gap. The Will fills the weak B gap and the Sam fills the strong C gap. Against zone teams, it is important to get downhill fast.

Dive flow tells us that we are getting a dive option play. The fullback is on a hard flow path while the tailback is on a fast flow path. Once again, our natural rules take over. The Mike comes downhill to attack his primary gap and handle the fullback. (Diagram 7).

The defensive end gets a veer release by his tackle or tight end. He bends hard down the line of scrimmage to tackle the dive. The outside linebacker (Sam or Will) has a fast flow path, so he fits tight to the hip of the defensive end and plays for the quarterback. This gap exchange happens naturally because of the rules of the Miami 4-3 Defense (Diagram 8).

Our safety will be responsible for the pitch against the option.

The 2-gap linebackers in the 4-3 Defense may seem complicated in the overall picture of the defense. Remember, each player only needs to be able to do his own job. Once you have the Miami 4-3 defense installed, the amount of time you have to spend on adjustments from week to week will be minimal. After 30 years, the Miami 4-3 Defense is just as effective as it ever was.

Joe Daniel is the defensive coordinator and offensive line coach at Prince George High School (VA). His web site – www.Football-Defense.com – includes over 300 articles and clinics on defensive football).